- Home

- Academic Reading Circles. Interview with Tyson Seburn by Paulina Christiaens and Review by Christina Chorianopoulou

Academic Reading Circles. Interview with Tyson Seburn by Paulina Christiaens and Review by Christina Chorianopoulou

23/03/2020 - 15:12

Tyson Seburn was going to be our plenary speaker at BELTA Day 2020, which unfortunately had to be cancelled.

He will be our plenary speaker for the online BELTA Day 2021 on 20 March 2021 but in the meantime here's an interview with him, which first appeared in the BELTA Bulletin, issue 10, Spring 2017.

Board member Paulina Christiaens talked with him about his book Academic Reading Circles.

The interview is followed by a review, written by Christina Chorianopoulou, who was a regular contributor to the BELTA Bulletin.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I have had the enormous pleasure to interview Tyson Seburn whose book Academic Reading Circles has cast a fresh light on reading comprehension activities in an ESL classroom.

P: Thank you for agreeing to this interview, Tyson. I would like to start with asking about the background for your interest in collaborative reading.

T: It stems largely from my time teaching at the university level, but even before my time at the university when I taught in general ELT contexts, the way most classes approached reading was very solitary.

Learners read a text, then worked on comprehension questions alone, then perhaps ended with discussion questions as a small group. Nothing about this process promotes deep comprehension or group work, both fundamental in our society. This was only compounded from my experience with the course that I teach at the University of Toronto: Critical Reading & Writing. Preparing students for the reading the need to do to successfully complete university assignments, I’d noticed how superficial the reading tends to be, particularly as learners default to focus on unknown vocabulary over concept. When left to do these readings without skill building or cultural schematic guidance, it can be an overwhelming and isolated experience.

My colleagues and I found that when we broke a text apart into different components, learners were able to dig more deeply into its concepts and vastly improve comprehension. This, however, is challenging to do alone. So working collaboratively in reading a text alleviates some of that burden, not to mention prepares them for group work that is common in many courses.

P: Could you tell us in more detail what ARC stands for and how it works ?

T: Academic Reading Circles (ARC) is an approach to intensively reading texts that is designed to guide learners towards a collaborative co-construction of text concepts by initially focusing on different aspects of the text. It breaks apart reading skills into specific techniques—things we all do simultaneously in our L1 reading—that learners focus on individually, then combines the efforts from the individuals in small groups to build a collaborative deep comprehension beyond what can be done alone.

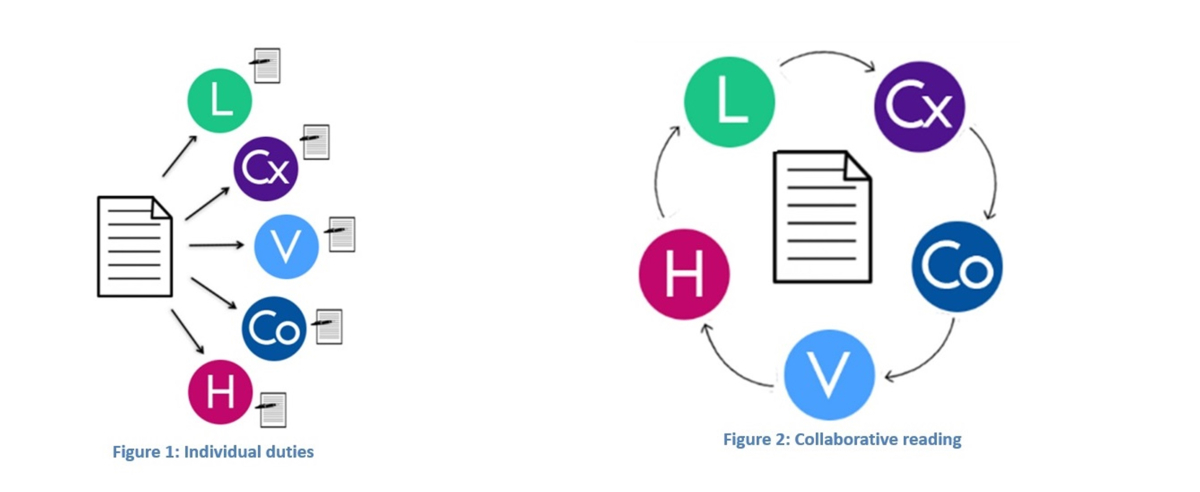

On successive texts, learners then rotate these duties so they become familiar with focusing on different aspects of a text, with the aim that once familiar with all ways to focus on meaning, they can more effectively read on their own when ARC is not practical to do in future class environments. In short, it begins with a common text all students are required to read; this follows with individuals reading it from one of five perspectives (Figure 1); after this, learners come together in groups of 4-5 to share and discuss what they’ve found from these five perspectives (Figure 2).

P: And what type of texts can you work with while applying ARC method?

T: Because of the teaching context where ARC was developed, it was created specifically with non-fiction texts in mind as these are the types of texts most often used in the programs undergraduate learners face in their university courses. This is why the more traditional literature circle activity is not effective or appropriate. As a result, it works best with magazine articles, journal articles, and reports on any topic.

In Chapter 3, I discuss these types of texts and considerations to make when choosing a common text in more depth.

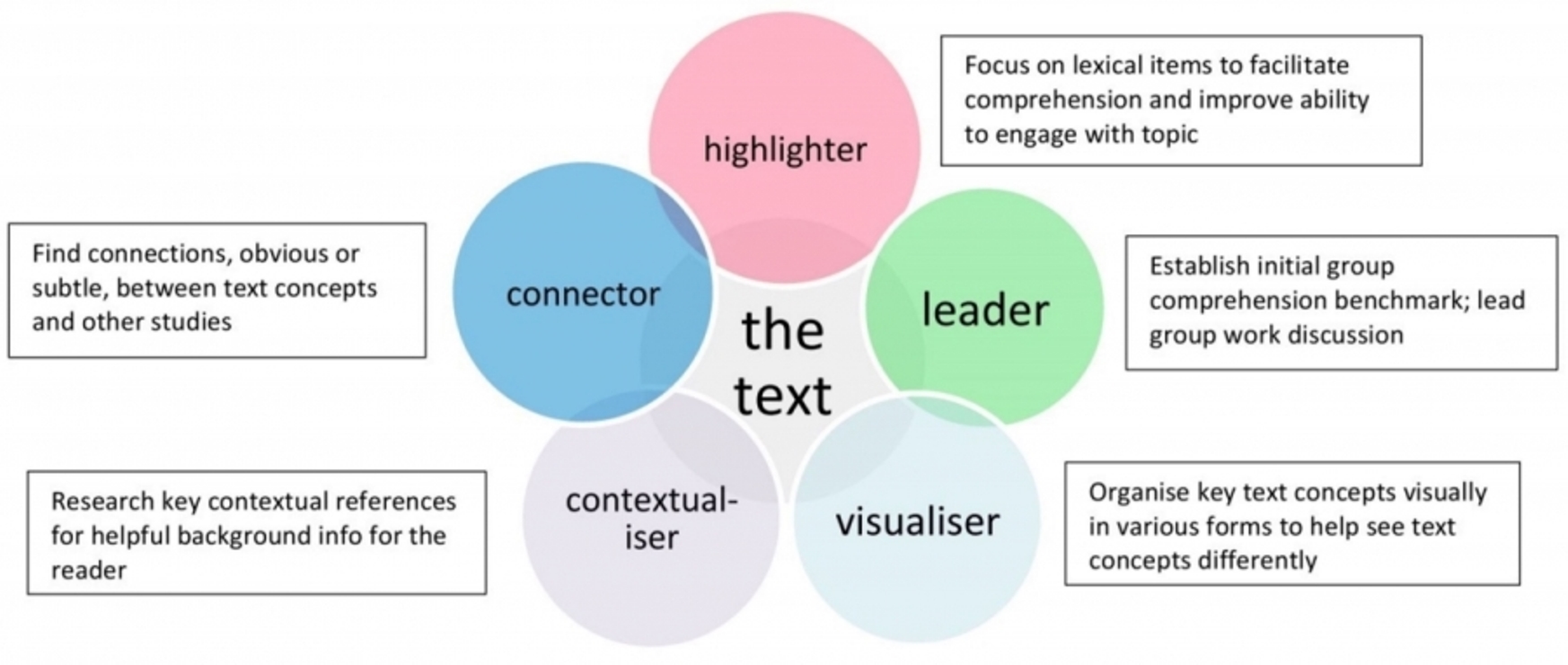

P: In your book Academic Reading Circles you describe five roles that constitute each circle. Can you tell us what these are and what purpose they serve?

Figure 3: Overview of roles

T: This overview (Figure 3) shows the five roles included in ARC and their primary purpose. Of course, with regard to specific duties and how to implement them on an actual text, this is discussed in great detail with examples in Chapters 4-8.

P: And if an ESL teacher, after reading your book, wants to implement the idea and start using ARC with their students, what are the absolute first steps that they should start with?

T: First, I would highly recommend reading the book thoroughly and then trying out the different roles on a text yourself to see how a learner feels. Looking at the role summary or even various shared versions of role duties I’ve seen floating about online isn’t enough. Different ARC roles lend themselves different weight depending on the content of the text you’re using. This suggests that the choice of text can impact how useful ARC is. It’s not always about length—some paragraphs alone can be packed with meaning. It’s not always about content—some topics are fundamentally more easily understood than others. It’s about identifying where your learners default to superficial reading and applying ARC in those cases.

Beyond this, I would strongly argue for scaffolding the ARC roles with learners on a sample text (or series of texts) together before letting them loose on a text themselves. Additionally, consider your course length. An ideal situation would be to afford each learner the opportunity to take on each ARC role at least once. Finally, keep in mind that ARC is not a replacement for other skill-building lessons. While it does introduce ways at looking at a text more deeply, it works best in conjunction with a syllabus, not replacing it.

P: In chapter 10 of your book you discuss Extensions. Can you give our readers some ideas what can be done with the text as a follow-up?

T: Chapter 10 divides ways to extend ARC beyond its basic process and components into three timelines: activities to do before, during, and after the group-work component (an ARC cycle is divided into selection of text, individual reading, group-work). What I find works most organically as a follow-up is for learners to use the text and the resulting comprehension they’ve constructed to a productive end. This could manifest itself as a reflective piece of writing on their reactions to text concepts, a summary of the text, an essay that synthesizes information from multiple texts used for ARC, or a group report which includes the findings of each role and reflection of the utility of each role.

Another productive skills possibility could include preparing a presentation about the ARC text and/or leading a discussion about it with the class. If we simply focus on using the text itself beyond the scope of ARC, I often incorporate it into other language lessons, like examining the author’s use of grammatical structures, chunks of language by frequency as shown in corpora, or techniques such as hedging. These lessons are what I refer to as existing inside a syllabus where ARC supplements.

P: And what are the results of using ARC? How is it beneficial to the students? What improvements have you noticed?

T: I know of several research projects in different universities currently being conducted on the various affordances resulting from ARC use in academic programs, not the least of which is one I am organising on my own groups for next year. In each, I’ve heard mostly about the positive qualitative data from both instructors and students on their experiences so far. I’m excited to learn more about all their findings in the coming months and years.

However, from a more anecdotal perspective, over the past six years, I’ve seen ARC largely achieve what it sets out to: a deeper and more accurate understanding of text concepts. This is demonstrated through learner ability to discuss, remember, and write about the text with deeper analysis than when done without ARC. It also improves awareness of digital literacies, referencing convention, and vocabulary building strategies. This has been noticeable both in written product about any of the ARC texts we’ve studied, but also in learner use of ARC strategies on successive texts.

P: My last question relates to the applicability of the ARC techniques. Do you see Academic Reading Circles employed in an ESL classroom not necessarily related to Academia – be it a language school, or secondary school – where one of the subject is English?

T: I strongly believe that almost any approach or technique that illustrates an improvement in language learners’ skills can be applied in some form across contexts. I do this whenever I go to conference talks, for example, that aren’t specifically related to EAP contexts. It is important to keep in mind though that this does require adaptations. ARC is created with learners in an academic learning environment foremost, so the duties and expectations of each role do aim to build skills specifically in that area.

Having said that, most any non-fiction text—be it a newspaper article, magazine, or even blog post—is embedded with many authorial techniques that are meant to convey meaning to a particular target audience. ARC roles, even taken outside the academic context, can be of benefit to a general language learning context to improve the ability to discover and uncover meaning.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Review of Academic Reading Circles by Christina Chorianopoulou

One of my best, most fulfilling moments in teaching has been sitting in the middle of a class of teenagers, listening and observing while a Literature Circle takes place; watching them engage with a written piece in a way I could not possibly pre-plan or expect, noticing how words drive their curiosity and thought or, sometimes, impede their understanding - and how they address this.There are many keywords I could use here, but collaboration and motivation seem the most appropriate; the same keywords I would have described all language courses.

Could such moments be experienced in other contexts?

I had never attempted this approach with groups of older learners and on non-fiction readings until recently - partly because I was unsure as to how to suggest it to students with little time on their hands and partly due to my distress of not having done this before with advanced learners.

When I got my copy of Tyson Seburn’s Academic Reading Circles and read it cover-to-cover as I usually do with every new book, my keywords were flashing out of the text in every chapter - I had to dig deeper into this approach and did so, both as a learner and as a teacher.

During the five months of working on academic texts with a group of teachers in my MA and monitoring several sets of ARCs in one of my Young Adult IELTS courses, this book has been an incredibly inspirational manual. With precision and attention to every significant detail, Academic Reading Circles manages to not only present a structured and solid approach to reading challenging texts, but also to cultivate and sustain high levels of motivation.

By using a sample common text, the book takes the reader through each step of implementation - from setting the learning background, to choosing appropriate texts, to a detailed description of every ARC role. The checklists given throughout are a very useful feature, as are the numerous suggestions for extension assignments and projects. Simultaneously, much of the focus lies in the groups, as they are the building block of an ARC and progress derives from the interaction among them. What I particularly like is the several opportunities for reflection and recycling of successful practices, as well as that peer feedback and assessment stand at the foreground.

Here are some reflections from participants so far:

“I realised that the way I visualized a concept was different to what the others in the group saw. It was hard to find a representation for all the group to agree on and understand, but they all helped me with their comments so next time I’ll definitely do better”

“I thought it was an easy text but when [the leader] gave us the discussion questions I couldn’t answer them. Not one of them. I had to read more carefully and every reference link too and again two (questions) I didn’t know”

“Reading in the group has been a big challenge for me because I’m used to working on my own and not have to wait for others, but now it’s much better because the other students say something I hadn’t noticed. This happens every time in the group and I don’t know how I miss these details yet but I’m trying”

BIOS

Tyson Seburn

Tyson is the author of Academic Reading Circles (The Round, 2015). You cand find Tyson's biography on his website..

Christina Chorianopoulou

Christina is an English and Greek language educator, passionate about project and game-based learning. With an academic background in Pre-School & Primary Education and being multilingual, her focus is always on building safe learning environments. Reflection and community are her building blocks; she blogs at mymathima and tweets as @kryftina .

She was a former President of TESOL Greece and a regular contributor to The BELTA Bulletin.